I would train myself to look at any object surrounding me, deconstruct it, and trying to figure out the way of building it with software by using a series of commands I would know about the 3D program. When I couldn’t figure out how to recreate a shape, I would investigate the best command to build it and add it to my toolkit.

After a couple of years, I had enough training on 3D tools and commands that I was able to represent almost any object I was encountered with, which in turn helped me better communicate my design solutions to my professors and classmates.

As a designer who now crafts digital products and services, I cannot longer afford to use the same toolkit I used as an industrial designer to explore problems and solutions, as they don’t have any boundaries or physical representations I can measure with my caliper.

I had then to change my tools and commands to a different toolset that would allow me to explore and solve digital problems.

Enter Mental Models.

A new toolset for new challenges

Popularized by Charlie Munger (considered by Warren Buffett a paragon and key player on the consolidation of Berkshire Hathaway), mental models are described as tools we use to represent the complexity of the world into a simplified version, just as different types of lenses we can leverage to help us remove the noise from the signal, and attribute meaning to what is important for us.

But, why are mental models useful?

No matter the word you have before designer in your job title, chances are you’re in the decision-making game, and when playing the game, it is also likely that sometimes you will find yourself in a position where you don’t have all the expected information to make a thorough choice, so you will need to make a bold move, an inferential leap. As Jon Kolko writes in his book Well Designed:

Because designers conceive of what does not yet exist, their process cannot be analytically proven until after the fact. That means that they must make intuitive or inferential leaps.

Mental models come in handy to make better decisions when enduring inferential leaps. As these set of heuristics come from a wide threshold of disciplines such as psychology, physics, statistics, and behavioral economics, they give you a multi-faceted prism to analyze your problem from different perspectives, thus reducing blind spots.

Cognitive biases are examples of mental models. Survivorship bias, for instance, describes how humans tend to focus on the people or things that overcame a selection process, thus avoiding the ones that didn’t.

During World War II, a Hungarian statistician named Abraham Wald was figuring out how to reduce the number of bomber plane failures during operations. Since he had data about the aircrafts that had returned, he could have decided to reinforce the areas that registered more damage. However, he recommended reinforcing instead the spots that have not been hit, as those might have produced the other planes to crash, and thus never returning.

That is how survivorship bias came into existence. Now, consider the following scenario as a way of acknowledging this cognitive bias into the UX practice:

The HR department of your organization approaches you because they want to improve the hiring experience and their internal processes when sourcing, recruiting and hiring candidates.

You’re eager to kick off the project, run some interviews, and maybe afterwardcreate a Journey Map to address the highlights and pain points of the process. Katelyn, from HR, is willing to help, and she says she can introduce you to 5 recent hires so they can share with you their experience and why they decided to join the company.

You review your mental models toolkit and remember survivorship bias, then you decide to tell Katelyn to reach out to the candidates who dropped out, in order to also consider the circumstances they had and not only the input of the ones who were hired.

Although the concept of mental models in user experience is often associated with the work done by Indi Young (who approaches them as a way to explore the way users navigate through systems and products), both Munger’s and Young’s avenues of mental models are worth exploring by designers who want to improve their day-to-day decisions while exercising our profession.

The following 3 models are focused on Munger’s approach, due to the potential extrapolation we can do of them to our field.

1 . The map is not the territory

There are two research findings of how the human mind works that have stood the test of time.

The first one is the brain as a pattern-recognition machine: the brain has evolved to always figure out meaning while experiencing the world, as well as jumping directly to conclusions.

The second one is the brain as an optimization machine: most of the time we’re operating through an automatic system (what Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman refers as System 1) which makes us take shortcuts in order to avoid cognitive overload and decision fatigue.

Yuval Noah Harari summarizes these two human mind conditions in his book 21 lessons from the 21st Century:

“Humans think in stories rather than in facts, numbers or equations […] The simpler the story, the better”

Problems arise when we are no longer able to differentiate the stories we tell ourselves and reality. Maybe because the story that we ingrained in our cortex was so compelling, that we just stopped looking for new answers. As Kahneman pointed out, we are blind to our biases, and we are blind to our blindness.

The Map is not the Territory is a good reminder of the potential risks we might face if we are not consciously aware of the interpretations and meaning we attribute to the world as we experience it.

As a UX Designer, I have seen how other designers focus too much on the tools and processes within their day-to-day work, that somewhere along the way they stop asking themselves the real purpose of using the artifacts.

- Designer: A new project, great! Let me schedule a Proto-Persona workshop. Being user-centered is the most important thing.

- Project Manager: On that note, I think it won’t be necessary as our main stakeholder will be the only user.

- Designer: Great. Make sure to invite her to the meeting. Let’s hurry up because I need to work on the journey map later, some job stories, then wireframes/mockups, and finally the prototype. My job is so hard and unpredictable, I know.”

The next mental model can be a good starting point to avoid falling into the trap of the map not being the territory.

2. A beginner’s mind

Heuristics, defined as rules of thumb based on previous knowledge, are the cornerstone of mental models. However, sometimes the answer we are looking for requires us to let go of what we we already know, in order for new knowledge to get in.

During an episode on the High-Resolution podcast, IDEO co-founder Tom Kelley elaborates on a concept he labels Vujà-dé (as opposed to Déjà-vu), referring to the act of reframing a familiar situation into a new one by looking at it with fresh, new eyes, thus revealing information not noticed before.

A beginner’s mind is the mental model to adopt any situation as if it were the first time you experience it, in order to uncover blind spots that otherwise would be hard to pinpoint.

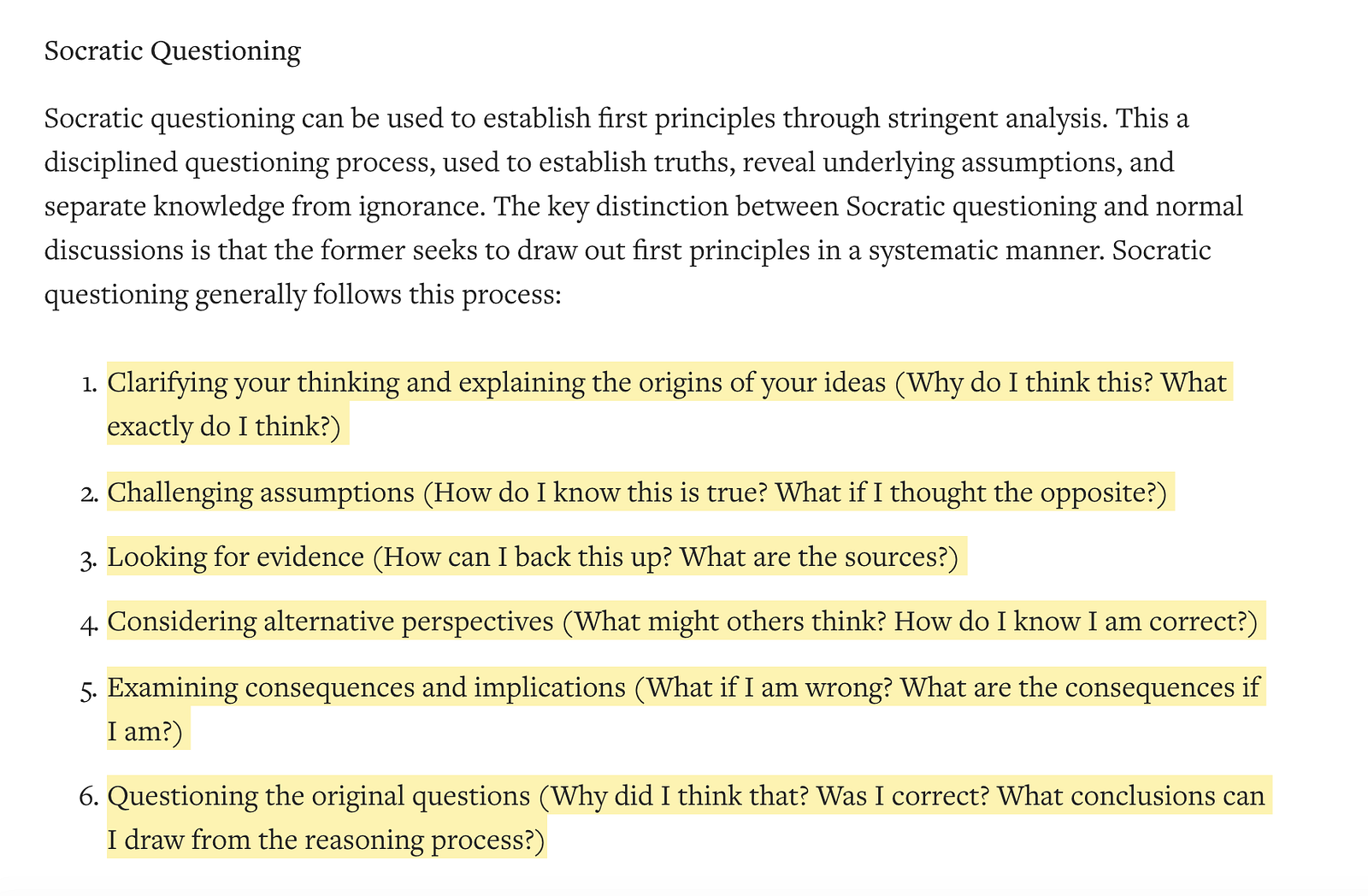

Although putting a beginner’s mind into practice might be harder than expected (it is actually more difficult to unlearn than to learn), Socratic Questioning is a great starting point to apply this heuristic in a systematic way. It is eloquently explained by Shane Parrish on his blog Farnam Street:

A beginner’s mind goes beyond asking why 5 times, as this line of thinking only provides a single-dimensional direction of causes, which might not lead to the best result. Other methods such as Fishbone analysis and Root Cause analysis might be more effective.

3. Thinking in systems

As technology evolves, our capacity to build more complex products also increases. More complex products derive in more moving parts, and when designers do not take into account all those moving parts and how they interact together, inconsistencies happen. Clutter is presented, and the end result is what Jared Spool defines as Experience Rot, a product full of non-sense features, confusing behaviors, and a frustrating experience.

In order to avoid this scenario, designers should be literate in systems thinking and permeate this mindset into their teams.

Russell Ackoff, a pioneer in the subject, illustrates the importance of systems thinking:

The performance of a system depends on how the parts fit, not how they act when taken separately.

As designers, we tend to assess our work by how proficient we are in the skills and abilities we have agreed as a community to grow. Information Architecture, Visual Design, Usability, are some examples. However, it can be naive to think that those disciplines will be enough to tackle down any problem we face in our career.

Systems thinking is our lighthouse when navigating through complex problems, as it forces us to think beyond our disciplines. As Ackoff points out:

[…] Disciplines do not constitute different parts of reality; they are different aspects of reality, different points of view. Any part of reality can be viewed from any of these aspects. The whole can be understood only by viewing it from all the perspectives simultaneously.

Adopting a systems thinking mindset means considering all the possible moving parts from the very beginning, up until the end of a project. To decipher those moving parts you might need to get out of your circle of competence and embrace problems as a holistic entity, not as a disciplinary one.

If you’re interested in leveraging your team to solve wicked problems in a systems-thinking way, I recently wrote about whiteboard exercises as a means to work in a trans-disciplinary way.

Takeaways

Mental models are not a replacement for evidence-based design or research; their biggest potential lies in how they help us navigate the world by creating meaningful and repeatable abstractions so we can make better choices without reaching decision fatigue. We should evaluate mental models by how useful they are, not by how right they are.

This is by no means a comprehensive list of mental models you can leverage for your work. Instead, it intends to serve as a prompt for you to put you into the business of creating your own latticework of models, refine them over time, and reduce the blindspots you might incur when grappling with complex challenges. The more mental models you include in your mental toolkit, the more situations you will be able to detect, and thus make better decisions.

A designer’s search for mental models

If you found this approach to mental models interesting, you should follow the work of Shane Parrish, Zat Rana and Charles Chu, polymaths who have invested more time and resources in mastering the craft of applying mental models to their lives. The following reads might be a good starting point.

- Zat Rana on Charlie Munger.

- 198 Mental Models analysis from DuckduckGo’s Founder.

- Shane Parrish on Mental Models

At Wizeline, no one is an island, and this article would not be possible without the invaluable advice of Rodrigo Partida, who inspired me to learn about Cognitive Psychology and Behavioral Economics. Thanks Ro!

P.S. Looking for help designing a mobile experience for your users? Wizeline was recently named a top California Mobile App Development Company on DesignRush.